The Glassmakers of Herat

In Winter, a thick cloud hangs over Kabul as people light wood and coal burning stoves to warm their homes. As a result the last few weeks Kabul’s weather has been described by Yahoo weather as ‘smoke’. We left the polluted capital, for the western city of Herat for a restorative break and to visit Hajji Sultan, the head of one of Herat’s last remaining glassmaking families.

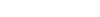

The glassworkshop sits at the base of Herat’s citadel – an ancient fortification, built by Alexander 1st, sacked in typical style by Genghis Kahn, and rebuilt again by Tamerlane. The workshop looks as old as the fortifications themselves. Around the kiln the walls are caked with thick black soot, and the ground littered with shards of broken glass.

The kiln had been fired two days before, and the walls of the kiln were still warm. We watched as one by one pieces of glass were caringly coaxed out of a small hole in the kiln with a long metal stick. Around 20% did not make it out in one piece.

The only instructions on making coloured glass to have survived since antiquity are found on a cuneiform tablet dating back to the 7th century B.C. The tablet describes the process step by step from the mixing of ground quartz, plant ash and copper oxide, to the method for blowing the glass and loading the kiln. The way they make the distinctive turquoise and lapis glass today remains almost identical to the 7th century description, although they melt down coloured glass found in the bazaar for some of their new colours.

These ancient techniques are not maintained for a love of ‘tradition’ itself. Next door to the glassworkshop we came across a tiny room with a camel strapped to a log of wood rotating in a stone bowl. Inside the bowl, the log was slowly crushing a mound of sesame into a fine pulp. ‘It is for the oil’ the man guiding the camel explained. In any other country, this would have been an attraction set up just for foreign tourists.

In Herat, they are no foreign tourists. The method is just the most economical method available. In the glassworkshop, the same relationship with tradition is true.

The glasses which survived the kiln will eventually be sent to Kabul to stock the family shop, but the local market for them has almost entirely disappeared. Cheap factory made imports from China have priced the glassmakers out of the market, and with no international flights, except to Mashad in Iran, Herat is isolated from markets abroad.

When we went to see Hajji Sultan that afternoon, he was not optimistic about the state of the industry. Lying in bed with a broken hip, he explained, ‘Before forty years, fifty years… many many tourist come to Afghanistan’, there were 12 factories back then. ‘Now 1 factory! No business, no foreigners, no tourists’.

Each glass is individually made by hand. Each has its own unique variation in shape and colour. Each has a soul of its own. It would be a tragedy if Herati Glass became another casualty of Afghanistan's latest war.

What to read next?

See more of our writing here

The mother of all slipper-ups

-

Edmund Le Brun

- 22.05.25

Having worked with our artisan partners for almost a decade now, they consistently meet the high bar we set for them. But in our quest for quality, we have learned some rough lessons along the way.

ISHKAR x Skye Jones

- 10.04.25

A collaboration with photographer and model Skye Jones, our new ring collection harnesses the beauty and power of horses, while paying homage to the rich history of Central Asian equestrian traditions.

Kandahar: The Second Home of Zoroastrianism | Shabnam Nasimi

-

Shabnam Nasimi

- 06.04.25

They call it the heartland of the Taliban. But for over 3000 years it has been Zoroastrian, Buddhist, and Greek — long before the Kalashnikov was invented.

Hand-knotted vs. Flatweave rugs | Afghan rugs explained

- 22.03.25

Ever wondered what the difference between a flatweave and a hand-knotted rug is? Keep reading to find out more about our Afghan rugs, and which one...

True blue | The history of lapis lazuli jewellery

- 13.03.25

Blue is one of the rarest colours found in nature. Up until the 18th century, whether you were a Pharaoh or an artist, there was only one place you...

Herat: The Pearl of Khorasan | Shabnam Nasimi

-

Shabnam Nasimi

- 27.02.25

Before Michelangelo, before da Vinci—Herat was already shaping the world. This ancient city sparked a renaissance before Florence—a place most have never even heard of, let alone seen.

The story of suzanis

- 13.02.25

Just-landed: a limited collection of richly-decorated suzanis. Hand-embroidered by craftswomen from Uzbekistan on 100% cotton fabric with fine silk...

Ghazni: Where the Shahnama Was Born | Shabnam Nasimi

-

Shabnam Nasimi

- 30.01.25

Three hours away from Kabul lies a place called Ghazni.

Why does the future look so bland?

-

Edmund Le Brun

- 23.01.25

And what does it tell us about our society?

Around 17,000 people once worked in the trade; now there is only one company left, with no apprentices. It’s hard not to feel misty eyed about the loss of this tradition. After all, it's a story we’re familiar with.

Balkh: “The Mother of All Cities” | Shabnam Nasimi

-

Shabnam Nasimi

- 25.12.24

Long before Rome’s power, Babylon’s hanging gardens, or the great palaces of Persepolis, there was ‘Balkh’—the shining jewel of the ancient world. ...

The craft of smuggling

- 12.12.24

A shipment of one of our wooden Jali trays was recently held by Border Force. When we finally received the package, we unwrapped the packaging to find that Border Force had drilled a small hole through the tray.

Kabul’s Forgotten Legends | Shabnam Nasimi

-

Shabnam Nasimi

- 28.11.24

The Kabul you haven’t heard of; where storytelling shapes its soul.

Moral conundrum? | Letter from our Co-founder

- 18.11.24

“I love my glasses and my husband wants to buy me some more. But I’m concerned about supporting a regime which is so oppressive to women. I’ve neve...

GUEST EDIT | Mathilda Della Torre

-

Guest Edit

- 29.01.24

Mathilda Della Torre is a designer and activist whose work focuses on creating projects and campaigns that transition us to a sustainable, fair, an...

GUEST EDIT | TARAN KHAN

- 15.08.23

One reason we wanted a physical ISHKAR shop was so that we could host events, talks, supper clubs, screenings, exhibitions, etc. A place to join wi...

GUEST EDIT | RUBY ELMHIRST

-

bookshop

- 24.11.22

Ruby Elmhirst is a creative producer, working with sustainable and socially conscious designers, artists and brands on unique projects across an array of mediums. Originally from London, her family lives between rural Jamaica and New York. This contrast has vastly informed her mission to promote opportunity, acceptance, education and diversity within design. For this edit she shares her interior wishlist as we get into winter and spend more time indoors.

THE JADID MOVEMENT IN SOVIET UZBEKISTAN

-

Exhibition

- 27.10.22

We spoke to Niloufar Edmonds, the curator of 'Bound for Life and Education: Sara Eshonturaeva and the Jadid Movement in Soviet Uzbekistan' about th...

My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird: Striking New Fiction by Afghan Women Writers

- 26.09.22

'My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird' is an extraordinary anthology of fiction by Afghan women writers, published in Feb 2022 by MacLehose Press in the UK...

NFT Print Capsule

- 04.07.22

For the Print Sale for EMERGENCY 2022, some of the photographers are offering one-off prints as NFTs, some for the first time!Including Matthieu Paley, Glen Wilde & Michael Christopher Brown.

EMERGENCY PRINT SALE 2022

- 22.06.22

On the 15th of August 2021, Afghanistan fell to the Taliban. As the world looked on, ISHKAR launched a sale of photographic prints to raise money for EMERGENCY Hospitals in Afghanistan. Like you, thousands of generous people contributed.

One year later the world’s attention has moved on. However the situation in Afghanistan is getting worse and worse. We’ve teamed up with an amazing group of photographers to run the print sale again. This is our opportunity to show Afghanistan that we still care. That we have not forgotten. This is our chance to direct crucial aid to where it is needed most.

Collection: Handmade in Pakistan & Yemen

-

Collection

- 14.06.22

Our handmade shirts and soap stone bowls, photographed by Charles Thiefaine on the island of Socotra, Yemen. November 2021.

The Houses of Beirut by Julie Audi

-

Julie Audi

- 28.03.22

It’s been a whirlwind for Beirut. Lebanon’s capital has spent the past twenty years trying to rebuild itself and its identity. I grew up in a city ...

Do we stay or do we go?

- 20.01.22

When Afghanistan fell to the Taliban we immediately paused trading with Afghanistan. After much deliberation, we have now taken the decision to con...

GUEST EDIT | SELMA DABBAGH

-

Guest Edit

- 23.12.21

Selma Dabbagh is a British Palestinian lawyer, novelist and short story writer. We asked Selma which ISHKAR pieces are inspiring her this winter. See here selection here:

Act For Afghanistan: Ways to Continue Supporting

-

Afghanistan

- 26.11.21

Now is not the time to stop reading, talking and thinking about Afghanistan. The situation continues to worsen by the day. So we've put together a few actions that you can take to make sure the world doesn't turn its back on Afghanistan, when it needs us all the most.

Mosul by Olivia Rose Empson

-

Olivia Rose Empson

- 06.10.21

Mosul, a city in the North of Iraq, is gradually remembering the steps to a long forgotten tune. Once a vibrant area with art, coffee shops and lo...

GUEST EDIT | CARMEN DE BAETS

- 01.07.21

Lebanese-Dutch Carmen Atiyah de Baets is CARMEN’s co-founder, a multifunctional guesthouse, kitchen, gallery and shop in the heart of Amsterdam.

Sicilian Street Food: Arancini

- 25.06.21

Sicily is famous for its street food, from freshly cooked calamari to crisply fried panella. One of our favourite Sicilian streets are Arancini....

Explore Neighbourhood Gems - Columbia Road

- 17.06.21

This summer we will be hosting different pop ups on London's Columbia Road, home to some of London's best restaurants, street bars and independent boutiques. Combine your pop up visit with some of these local highlights:

GUEST EDIT | IBI IBRAHIM

- 25.03.21

Ibi Ibrahim is an American Yemeni curator, artist, writer, filmmaker and musician.

Know Your History: 5 Afghan Women You Should Know

-

Afghanistan

- 08.03.21

Words by Shamayel, founder of Blingistan. Illustrations by Blingistan + Daughters of Witches. How many of these five extraordinary women have you h...

Blingistan as in the land (-istan) of Bling

-

Guest Edit

- 05.03.21

We spoke with Blingistan founder, Shamayel, about the need for playful, bold, conversation starters that can change the narrative about Afghanistan.

GUEST EDIT: JAMES SEATON

-

Guest Edit

- 28.01.21

We invited James Seaton, co-founder of TOAST, to cast his well trained design eye over our collection and to be our very first guest editor.

Who gets what: our product pricing explained

-

ISHKAR

- 26.01.21

How, we are often asked, can a box of six glasses made in Afghanistan, one of the world’s poorest countries, be sold in London for £80? In this blog post we aim to show you who gets what and why.

A letter in the time of COVID-19

-

ISHKAR

- 06.03.20

This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumours. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma. We are all in this together, and we can only stop it together.

Paradise Lost & Found: Babur Gardens

-

Lucy Fisher

- 03.05.19

A guest blog by Lucy Fisher I would like to hazard a guess that the first image which comes to mind when asked to think of Afghanistan is probably not a garden in full bloom, carefully tended to by a team of dedicated local gardeners. Despite the horrific turmoil...

A Conversation With Ibi Ibrahim

-

Interview

- 02.02.19

A guest blog by Louis Prosser After almost four years of incalculable destruction and suffering in Yemen, you might think that the last sparks of beauty and creativity had been crushed. You would be wrong.Ibi Ibrahim is a 31-year-old artist working mainly in photography and film. He is Yemeni,...

The ultimate sacrifice

-

ISHKAR

- 02.01.19

[replace_with_featured_image] Fig 1. Babur gardens [source unknown] Fig 2. One of the hospital's where Dr Jerry used to work[source unknown] W...

Timbuktu: A wild story of Myth, Renaissance, Rescue & Ruin

-

ISHKAR

- 16.10.18

‘I don’t care if you’re in Timbuktu,’ we might say. ‘You’ll be here tomorrow or else!’ Or perhaps, ‘He’s flirted with every girl from here to Timbuktu!’ It means something like God Knows Where, or A Million Miles Away.

War Rugs

-

Louis Prosser

- 08.10.18

'Bebinin, bebinin,' insisted Parsa. I was in the royal city of Esfahan, which the Persians call 'nesf-e jahan' ('half of the world'). In a cramped bazar beneath soaring domes and arches, I was in a world of carpets. 'Look, look: apache, apache!’ The word rang a bell (an American tribe?) but it took me a few seconds to see. It was a truly beautiful piece.

The Pin Project Viewed from the Ground: A Guest Blog

-

Sofya Saheb

- 10.07.18

The Pin Project is an initiative ISHKAR launched on Kickstarter last year. We raised over £63,000 to provide jewellery training and work for displaced people living in Burkina Faso, Turkey, Jordan and Afghanistan.

Soqotra: The Evolution of an Alien Island

-

ISHKAR

- 28.05.18

Give a child a packet of crayons and tell them to draw a fantasy island, and they might well conjure up the Yemeni island of Soqotra.

LET'S WORK IT OUT!

-

ISHKAR

- 12.12.17

As humans, we crave order. For many, productive work provides this structure. The world around us might be chaotic. But with work we can, at least at times, control what we do in a way we are rarely able in other parts of life.

Tradition as Radical

-

ISHKAR

- 25.07.17

At the beginning of this year, Flore and I found ourselves at the world trade fair for homewares, Maison et Objet in Paris. After a morning of walking through the colossal trade halls we were quite frankly bored of looking at objects. We were just about to escape and get a coffee when we came across Sebastian Cox’s stand.

Handmade - so what?

-

ISHKAR

- 20.07.17

Once a hipster trend, the desire for handmade goods has become thoroughly mainstream. It can be seen from the meteoric rise of Etsy, right through to proliferation of the word ‘artisan’ on products ranging from shoes to bread. Handmade products tend to be more expensive, and by no means assure better ‘quality’, so what’s all the fuss about?

Risk: Sliced, Diced and Sprinkled On Top

-

ISHKAR

- 13.07.17

As wedding season approaches, we have been getting an increasing number of exasperated customers asking when our most popular glasses will be back in stock again. Well, here's the honest answer – we have NO idea.

Traces of Aleppo

-

ISHKAR

- 08.05.17

[replace_with_featured_image] Fig 1. Traces of Aleppo [source unknown] Zaina Sabbagh bought her first wooden printing block when she was 14. Sh...

Timbuktu & Back

-

ISHKAR

- 05.04.17

I remember singing a nursery rhyme about Timbuktu when I was in primary school. I can’t remember what it was now – was it ‘from Kalamazoo to Timbuktu’? – but I remember the images clearly. A fabled desert city at the end of the world where Arabs and Africans would meet to trade salt and gold, and in the cool of enormous mud structures blue robed scholars would scribble marginalia in great gold embossed manuscripts.

Can 'crafts' really drive serious economic growth?

-

ISHKAR

- 28.09.16

Yet we would be wrong to think of crafts as a small sector at the fringes of the global economy. Far from it, crafts are in fact the second largest employer in the developing world, and have a proven track record of leading a number of developing world countries towards developed world status.

Want to help Afghanistan? The case for buying over donating

-

ISHKAR

- 12.09.16

The World Bank has ranked Afghanistan, as the 177th easiest country in which to do business with in the world. Unfortunately that was out of 188 economies. Here’s a quick barrage of some more dismal figures… In 2014 Afghanistan’s economy lost a third of its value, and annual economic growth slowed from 14% down to 1.5% where it hovers around today.